Compost tea (it's not for drinking)

How you can stretch the yield of your compost even further, plus make your plants + soil happy.

Today I want to talk to you about one of my favorite compost innovations: compost tea. Compost tea is, essentially, a liquid version of your solid compost. It’s made by suspending a small amount of finished compost in water, and letting it steep. The result is a concentrated mix of the macro- and micronutrients that plants and soil need in order to thrive, in a readily applicable form. (You can spread the two gallons of compost tea much further than the few handfuls of solid compost you used to make it.) You can apply compost tea as a soil drench or a foliar spray, i.e. drenching a plant’s leaves directly, or a “sprench.”

Plants and soil love it all.

I like compost tea because it’s easy to make, fun to experiment with, and (above all) highly effective. My teas have returned vigor to sun-ailed vegetables, helped them combat infestations, and improved the water-holding capacity of my soils—all without the use of nasty chemicals or any products that would, you know, result in nitrogen run-off in my local water supply. Compost tea also takes about $25 worth of materials to make. I DIYed my compost tea kit together with a new bucket, an old BBQ grill, some bags for making nut milk, and a few small air stones—but you can buy ready-to-go kits from places like the Compost Tea Lab, at slightly more cost.

I’m a big believer in compost tea because I’m a big (big) hater of what you see typically sold in garden stores. By now, we all know that non-organic fertilizers and pesticides are contributing to ecological castrophe, but they’re also wildly ineffective across the long term—destroying basic soil health in favor of cartoonishly-extreme short term yields, and resulting in an ever-growing dependency on costly external inputs for basic plant growth. Despite that, your local Home Depot (and ilk) continue to stock row-after-row of expensive and deadly chemicals and sell them to you as the “standard” in yard care.

The insanity must stop!

Compost tea is a handy, natural, and affordable solution to most of the problems that chemicals claim to solve—so long as you’re willing to put in the work to make a quality brew, spend a little time tweaking your formula in order to fit your plant’s specific needs, and emotionally deal with the fact that sometimes you will lose a bloom or two to bugs.

How to make compost tea (basic)

You will need:

air stones

air pump (the kind you use in a fish tank)

aquarium tubing (this usually comes with the air pump)

a bucket

compost

a mesh bag

This is not a “must have” — but I have a filter on my outdoor hose that removes chlorine, which can suppress microbial populations, from my water. If you don’t want to drop the $50 on a fancy filter, though, you can let your water sit for a day before using it to make the compost tea. The chlorine will evaporate.

First, collect some of your finished compost into your mesh bags. You don’t need to fill the bag to the top, about 3/4 full is just fine. Then, fill your bucket about 3/4 with water. Begin aerating the water with your aquarium pump and air stones. Rest the bag of compost in the water, gentle squeezing and massaging it, so that the bubbling water fully penetrates the compost. Let it all sit for 24-36 hours. Then, remove and use the liquid for your plants and soil.

That’s all there is to it.

You can tweak your recipe by adding a number of (natural!) substances to promote the growth of aerobic bacteria or fungi, depending. For example:

fish poop

kelp fertilizer

humic acids

seaweed extract

molasses

worm castings

powdered oatmeal

white sugar

For one bucket, you won’t need more than an ounce or so of each. (It will surprise none of you to hear that I never specifically measure what I add to my compost tea. Eyeballing it works fine, for me.)

Fungal vs bacterial brews

Based on what you’re growing, you might want to use some of the add-ons listed above to tweak your brew to be more fungally or bacterially-dominant. Not sure which your plants will prefer? An easy short-hand is to think about how long of a lifecycle your plant has—annuals, like vegetables, flowers, and grasses, usually make better use of bacterially-dominated brews, while fungi prefer to partner with perennials, like trees and shrubs.

From the list above: bacteria prefer simple sugars that are easy to break down (like molasses and, obviously, literal sugar), and pretty much everything else encourages fungal growth. Keep in mind that compost tea, like your compost, is all about balance, though. Even when brewing a bacterially-dominant tea, add at least a tablespoon or so of humic acids or kelp fertilizer (something to encourage fungal growth!). Afer all, you want bacterially-dominant tea—not pure-bacteria.

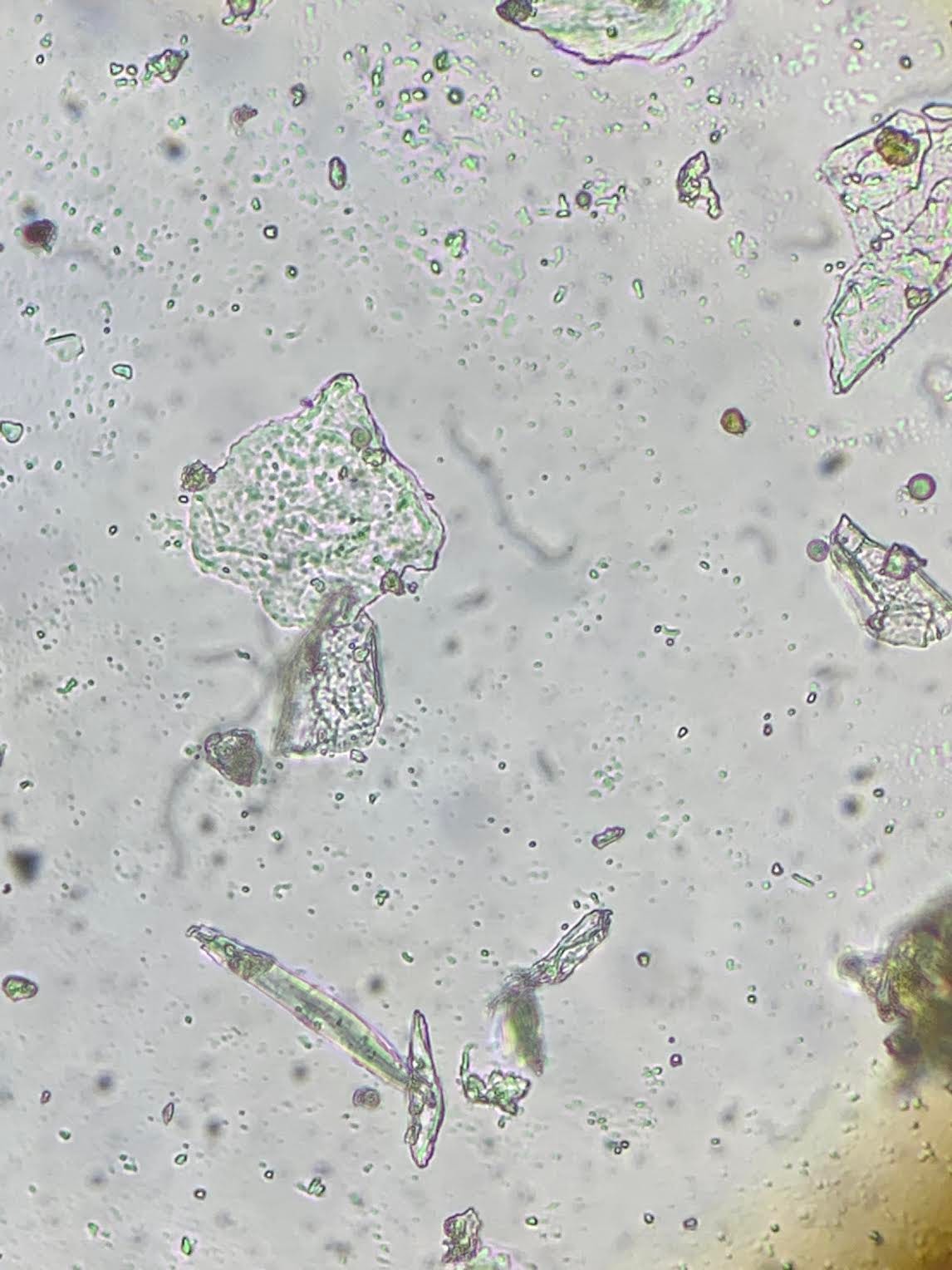

Checking your brew

When I’m done with a brew, I do like to check it out under my microscope—just to see what’s going on. I look for signs of life (jiggling bacteria, squirming nematodes), and check for any indications that my brew might need more or less aeration (like the presence of anareobic specices, which mean I need more bubbles in my brewing process). I am greatly aided in my interpretation of microscopic results by my friend Andie Marsh, who I’ve interviewed here before.

Even if you’re without a microscope, you can usually gauge the quality of your brew by how your plants react. Do they look vigorous and up right? Greener? Do you spy new leaf growth? All of these are signs that your brew is doing the right thing. Simple soil tests can also help guide you.

Got any compost Qs? As a reminder, just reply here and I may answer in a future edition.

Love,

Cass

Hmmmm. I do love to be educated about compost. After reading about your tea method you have made me curious about the ‘tea’ that runs from my worm compost. I have the worms in a grey storage container (to keep it dark for the worms) which I have poked with hundreds of holes. I put that container on bricks which sit on a another container lid to catch all the liquid (tea) that oozes out. About 4 times a year I mix that brew with water and feed my plants. After reading your article I want to borrow your microscope because I am curious if there is that kind of life in my tea. Btw, you are the only one I know who owns a microscope. 😆

Great timing - I tried my first tea brew about 3 weeks ago and it worked great. That's a great tip about gassing off the chlorine, I just let my bucket sit for a day first - but now it really has me wondering about how much chlorine kills all those lovely microbes in my garden when I'm just doing regular watering..