My favorite book "about" composting...

... was written by Gary Larson 👀

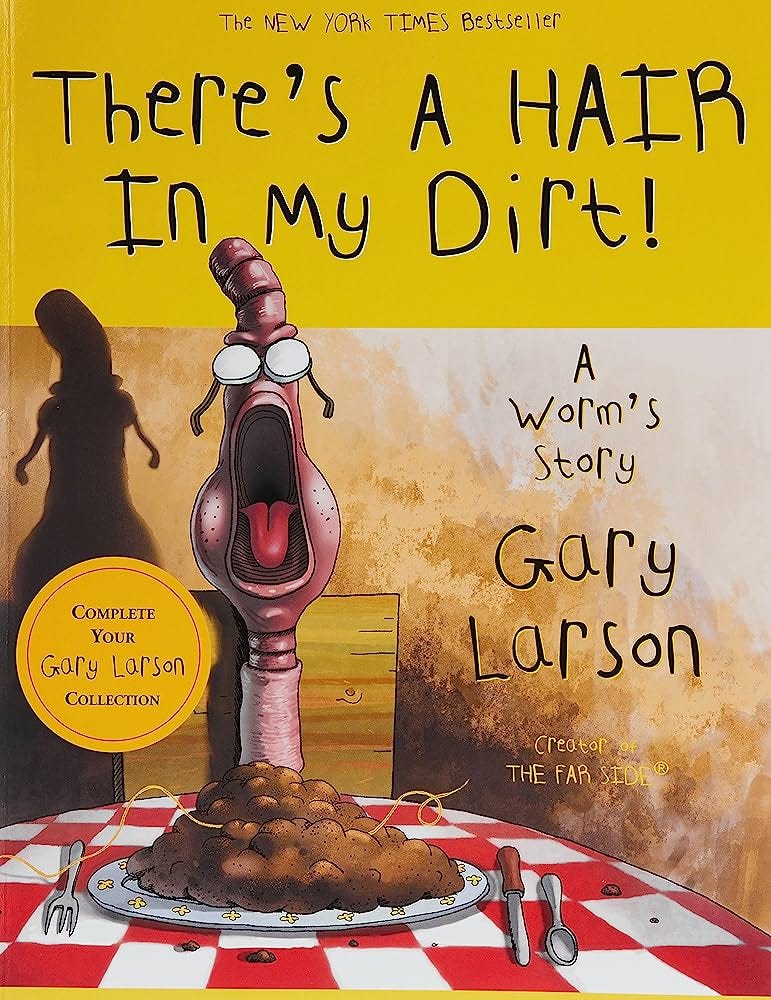

When I was a kid, I was a big fan of Gary Larson. I sought out his comics religiously, scouring local newspapers and checking the “humor” section at the used bookstore on a near-weekly basis to see if anybody might have dropped off a collection for sale. None ever surfaced there. What I did find, though, was a copy of something called “There’s a Hair in my Dirt!”, which turned out to be a children’s book Larson had written about why a piece of blonde hair had appeared in a worm’s dinner. The volume was published in 1998—I was 12 when I first read it—and, candidly, it changed my life. Not only was it brilliant and cynical, qualities I would forever aspire to, but rarely achieve, it put into words something I had only just begun to comprehend about people. Namely, that we often “loved” things at the expense of understanding them.

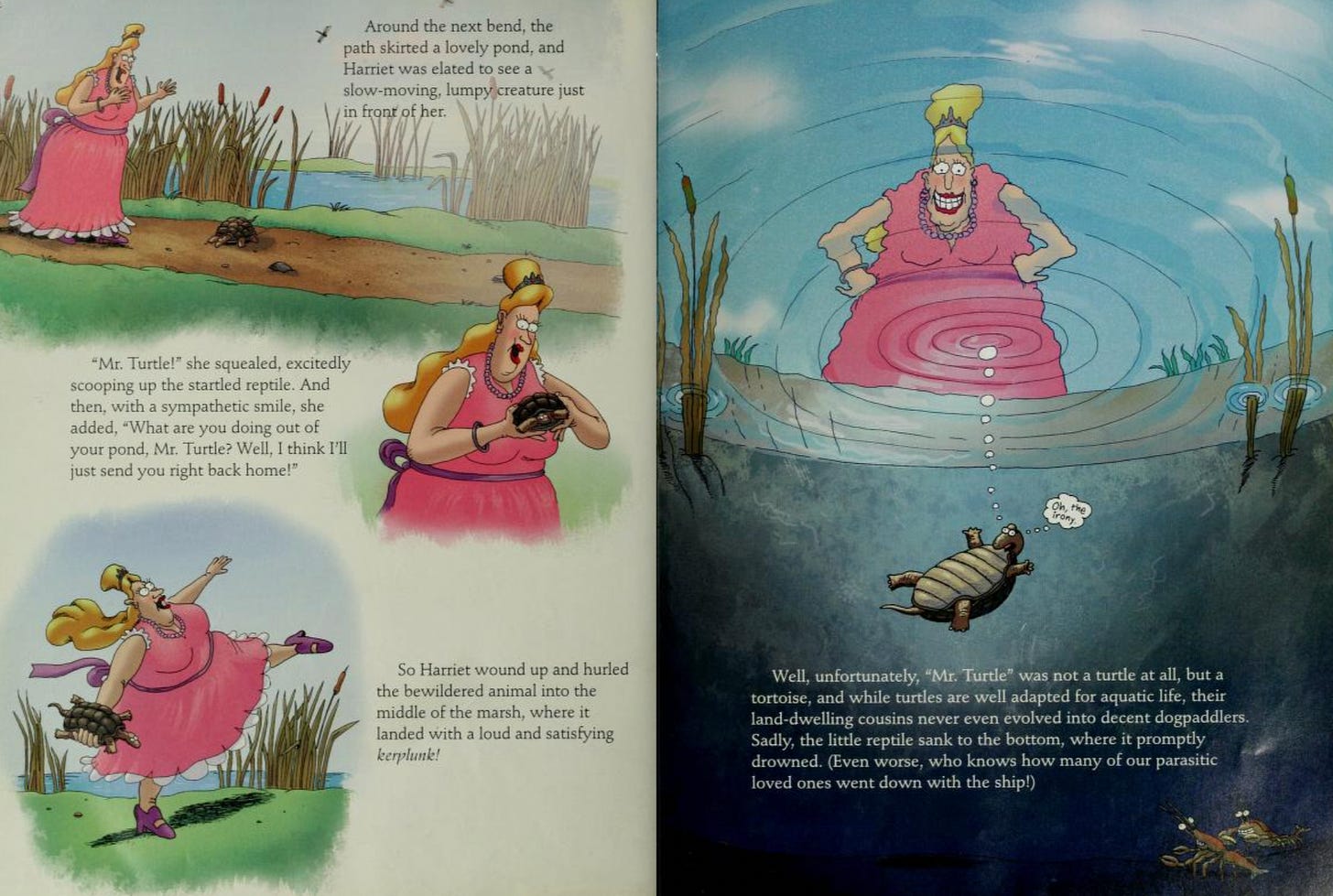

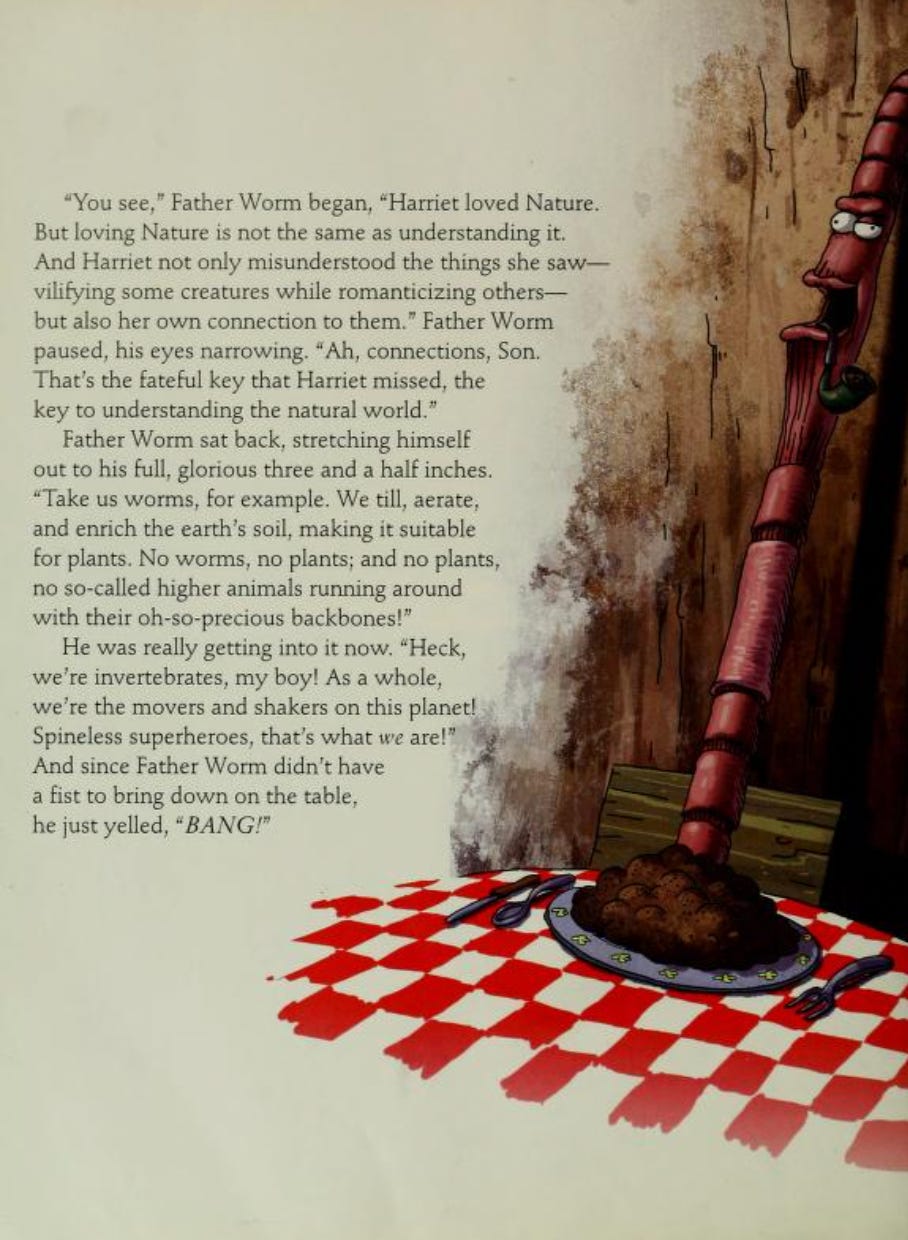

“There’s a Hair in my Dirt!” is the story of a worm who demands to know why his dinner is ruined. His father explains that a young woman once roamed the forest above them, encountering and chronically misunderstanding the surrounding nature, until one day she foolishly dies after “saving” a small, disease-ridden mouse from being eaten by a snake. The titular hair in the dirt is there because (spoiler alert) the woman’s corpse is decaying above the worm’s family home. You can see how this would strike a budding composter as a particularly gratifying end point.

Larson takes great pleasure in skewering his protagonist for her naive and disinterested reception of the plants and animals around her. She feeds squirrels because they’re “cute,” unaware that they’re an aggressive and bullish species that has overrun the native variety, thinks dragonflies are “dancers,” ignorant of the fact that she’s watching them hunt and devour other insects, and observes a forest fire from a distance with “horror and grief,” having no idea that fire is a natural and beneficial part of a healthy woodland ecology.

As a child, I found this story deeply validating. In my hometown, I had often observed adults “helping” nature in ways that, when not outright destructive, seemed at least illogical and bizarre, but I had always assumed that the issue was my perception—not that what anybody else was doing was wrong. One particular memory stands out, from when I was about seven, and came upon a woman in a park by my friend’s house who was stamping a snake to death in an effort to rescue a mouse it had already partially eaten. “Let her go!” she kept crying, in genuine distress. “Let her go!” Something about the situation felt fundamentally incorrect to me, but I was too frightened and unsure to say anything. Instead, I backed away slowly.

Reading “Dirt” changed all that. Larson’s book anointed my perceptions as correct and even worth speaking up about. I felt authorized to be curious and to question what I was told. I also felt more able to understand why the woman killing the snake had felt so misguided to me, even at age seven. Predators eat, that’s how things live. The snake had not been doing anything wrong and certainly did not deserve her intervention. At this moment, I first grasped the connective tissue between life and death—the value each held for the other.

“Dirt” was wildly successful in its time, you’ll have noted the “bestseller” text on the cover, but seems to have since vanished, despite Larson’s enduring popularity. I always found that a shame. Its ideas are still resonant and its text would not be out of place, even today, on the Instagram account of any ecological “activist.” (Even though that very same activist might easily supplant Larson’s well-meaning protagonist in an updated version of this story.) Luckily, these days you can read the entire thing, for free, by borrowing it from the Open Library. I’ve also included some of my favorite pages below for your enjoyment.

Hope it inspires the composter in you. :)