Watching nematodes eat

Or, a very (very) microscopic look at how decomposition helps create new life, featuring the team at LA Compost

When we first look, we immediately see it:

“It” looks like a long, translucent ribbon. Its insides are patterned with shadows, rumpled and oblong shapes arranged tidily within its frame, and one end appears to be lopped off at an angle, creating a slightly dimpled edge. It is gently waving, as though saying “hello.”

“Oh,” says Lynn Fang, a soil scientist who works with the community nonprofit LA Compost. “It’s feeding.”

Indeed, a small dot can be seen bouncing along the ribbon’s boundary, triggering a gentle undulation in response. We crowd around and watch for a few breathless moments, wondering if we will see a meal, but the dot bounds away again, energetic and unbothered.

Disappointed, we sit back.

What Lynn and I are looking at is a tiny pinch of my compost, diluted in water and placed under a microscope. The ribbon is a nematode and the dot is an aerobic bacteria. Both are keystone members of any healthy compost’s microbial population and it’s exciting to see either of them, at all, but had we happened to catch the nematode successfully grabbing a snack—what we would have been witnessing is one of the most critical interactions in the whole process of decomposition.

(If that sounds like an overstatement, it’s not.)

Nematodes, like any other living entity, need to eat in order to survive. Some eat bacteria and others prefer fungi. Some feed on plants, others feed on each other. Some have a varied diet that includes all of the above, simply based on what’s available. (They’re called “omnivores.”) When nematodes consume bacteria or fungi, though, something interesting happens. Because those microbes are higher in nitrogen content than the nematode physiologically requires, the nematode ends up excreting the excess as waste material. That excess nitrogen, taking the form of ammonium, is then available again as a nutrient that can be utilized by plant roots.

This is just a tiny and singular interaction, but it is happening alongside hundreds of similar others, at the scale of millions-(sometimes-billions)-per-teaspoon of finished compost, and it is one of the reasons why all the dead stuff that goes into your pile ends up coming out the other side as fertilizer for your plants. Nematodes do lots of things besides poop, of course. They provide food for larger species, consume and kill pathogens, and can even carry microbial spores from one part of the pile to another, distributing them more evenly throughout a heap.

They are, truly, the secret superheroes of compost.

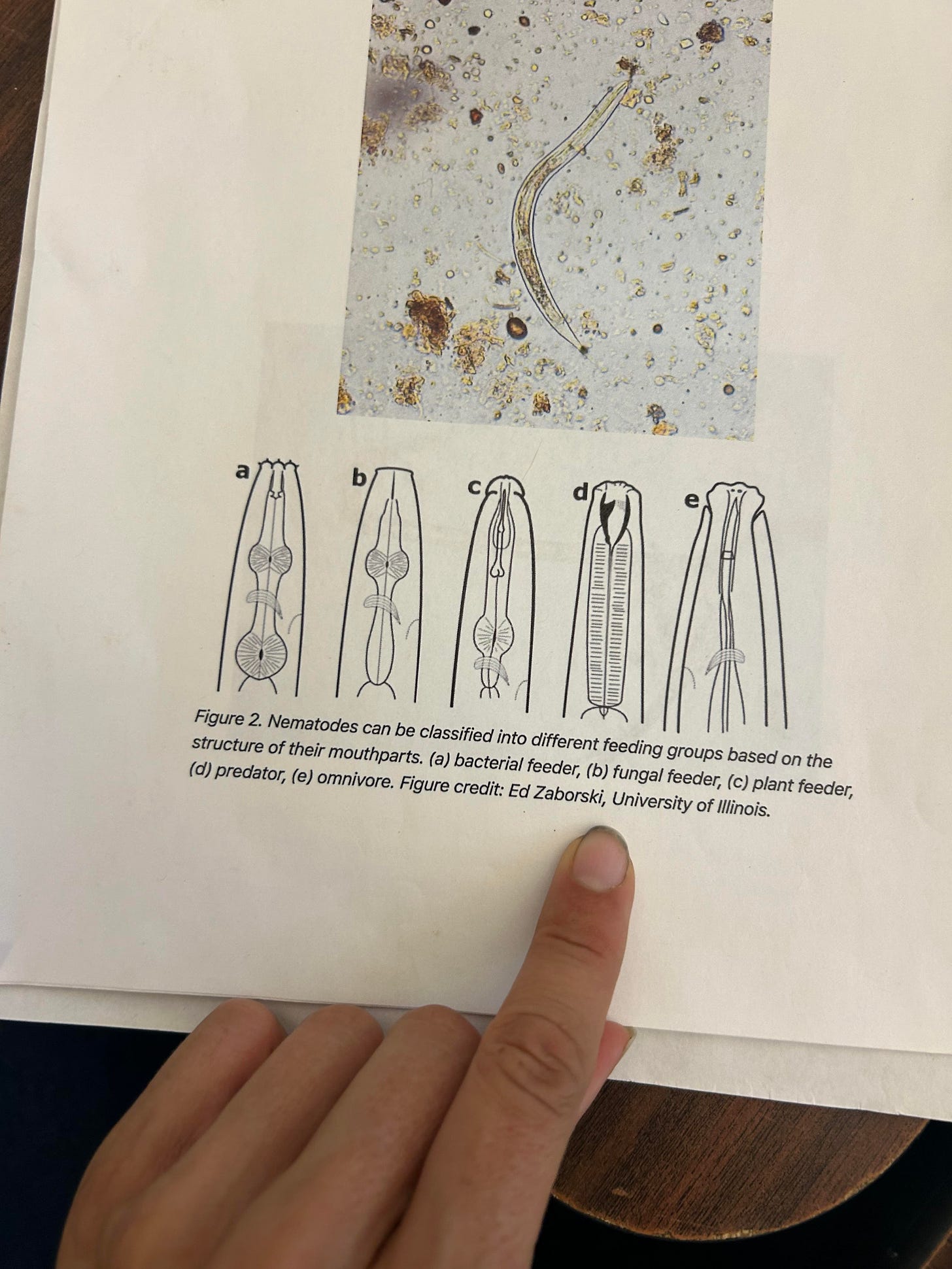

In the lab, our own nematode remains on the screen before us. Absent the activity of the aerobic bacteria, it grows still and seems tired. (I’m projecting.) Lynn, myself, and her colleague Maggie all examine it closely. Through them, I learn that different types of nematodes are most easily identified by the shapes of their different parts, particularly their mouths. For example, bacterial feeders have three simple ridges with small spiky-looking tufts emerging from each, plant-feeders look like tiny penises, and fungal-feeders—like the one, I now recognize, we are looking at—appear to be cut straight across at one end.

I can’t help but be a little amazed.

There’s reading about things in books and then there’s encountering them in real life—actually seeing them as they exist. Sitting in the lab with Lynn and Maggie, watching our nematode wave, I felt bright excitement coursing through my body. I have spent the last four years making compost or reading about compost or talking about compost, in some capacity, almost every single day, but I had never looked at my own pile before. Not like this. What I got to see was that the inner-workings of a compost are a matter of sheer abundance, the totality of which defy easy synopsis. What we had ultimately witnessed was a part-of-a-part-of-a-part of a complex and infinitely mysterious whole.

A simple nematode.

I loved it.

Notes on this post:

If you want to read more cool stuff about soil, I highly recommend Lynn’s Substack. Lynn is an amazing human and a huge resource to the community. (I can’t tell you the number of times I heard about her before I finally got to meet her.)

The compost microscopy session that this post springs from was part of a community initiative hosted by LA Compost. LA Compost is hands-down my favorite LA-area nonprofit. They are doing amazing work for community composters everywhere, and can be supported in their mission here.