I had a conversation with a farmer recently who was surprised, although pleased, that I wrote about compost more from the perspective of waste management than garden fertilizer. As a farmer, the principal purpose of his own pile is to feed his crops and nourish his fields. As a city-dweller myself, though, working in compost is about managing my waste while reducing harmful methane emissions from my local landfill. In fact, working in compost has made me somewhat obsessed with waste. Not just my own—but the whole system.

How does waste work?

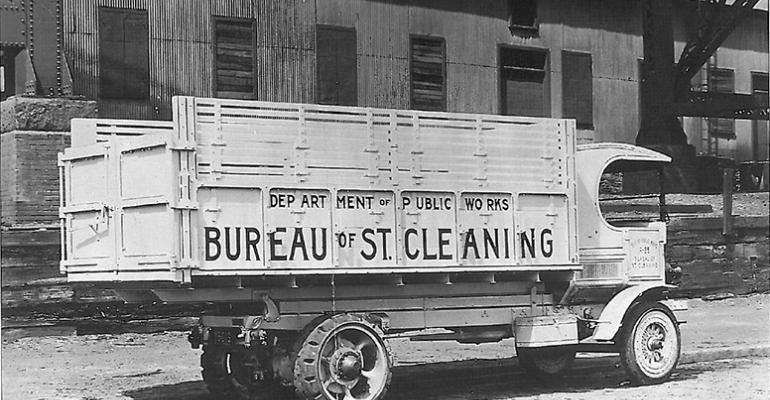

Well, in America (not surprisingly) the answer is: poorly. It’s a cumbersome system organized around a set of crummy incentives that protect and encourage the voluminous production of trash, with the landfill as a central feature. Why? Before World War II, waste management was a highly local affair with very low buy-in costs. Dozens of operators worked in every city, managing fleets of 5-10 open bed trucks, collecting and sorting waste, and dumping anything not reusable into nearby private or local landfills. There were pros and cons to this approach. Pro: the open bed trucks allowed for easy sorting of materials, and most stuff didn’t actually get thrown in thelandfill. Con: the landfills were poorly managed, open-air piles that freely and egregiously polluted the surrounding areas.

After World War II, things started to change. Namely, the suburbs saw massive and sudden expansion as veterans returned and, aided by federal benefits, bought up homes and started families. They became a politically powerful bloc and one that opposed the existence of pollution-happy landfills in their collective backyards. Some were closed. Others were built, but miles away from the urban centers they were meant to serve. Simultaneously, recycling—the poster child of good citizen action during the war—saw a steep decline in popularity. The amount of stuff getting tossed in the trash went up, and it had to go further away to be dealt with. More complex infrastructure was required.

The rest is a common story for any country operating under capitalism. With more complex needs to meet, and a system of more sophisticated independent contractors spreading across the country (~12,000 in the 1950s), plus businessmen with access to more money, the opportunity for vertical integration emerged. Today, just four private waste management companies own over 50% of the waste hauling market while owning 75% of permissible landfill capacity in major metropolitan areas. Business is lucrative, and the remaining businesses are highly protective of their profits. Their primary mode of protection?

Exclusive franchise agreements.

Across every city in America, municipal leaders are tasked with managing the waste in ways that are both streamlined and considerate of community health. Often, they handle this by granting a franchise agreement to a third-party contractor who is exclusively responsible for waste management across a designated residential area. That means no competition is allowed. One contractor, and one contractor only, is responsible for trucking all the waste out of your neighborhood, and into the local landfill. (Like the “open bed truck systems” of yore, this approach has both pros and cons. Pros: it minimizes congestion from trucks (plus wear-and-tear on neighborhood infrastructure), and it’s much more operationally efficient. Cons: Monopolies trend toward corruption and abuse, and when a company’s business model is “more trash, more money”—they end up wanting to protect (if not encourage) the creation of garbage.

That’s why so many exclusive franchise agreements have some, ahem, rather interesting provisions. For one, some have requirements for the amount of waste that the company will handle each week. If that threshold is not met, the city is fined the difference. Second, any business that can be seen as encroaching on “waste management” can be sued to stop. This happened recently, when a franchise agreement holder sued a company called Ridwell for collecting waste in a Portland, Oregon neighborhood, despite the fact that the waste Ridwell was collecting wasn’t accepted by the waste haulers themselves. In Pasadena, an organics waste collector was forced to close after receiving pressure to apply for a franchise agreement in order to operate, which came with too hefty of a fee for them to manage.

As you can imagine, the stakeholder that suffers most in this equation is the environment. The industry is existentially threatened by the existence of environmentally-friendly alternatives like composting, recyling, or upcycling—and will behave aggressively when threatened, even by well-meaning community initiatives to reduce waste and green our cities. Add in that the waste hauler game is, politically, on par with the NRA (there are bribes, boy, are there bribes) and you get a waste management system that is both really bad, and entirely stuck in one place.

It’s tricky.

But sometimes it gets better.

5 years ago, Los Angeles updated their franchise agreement to work with a program called Zero Waste LA, which requires:

“…commercial haulers to reduce landfill disposal by one million tons/year by 2025, requires that all 64,917 commercial waste accounts in the City be given a blue bin for recyclables and a green bin for organics, that all trucks be clean fuel (i.e. fueled by compressed or liquefied natural gas) vehicles, and that the franchisees partner with food rescue and reuse organizations.”

This is a promising move forward in a complex system. It’s rearranging the incentives toward efficient management versus maximum output. Community awareness also helps. It’s my guess that maybe… none of my friends have any clue about exclusive franchise agreements (why would they?), but they do have a clue about methane emissions, and a strong desire to reduce them. Composting is always a valuable step, but so is knowledge, and building strong relationships with your local city council people—the very same ones that are voting on waste hauler mergers and approving franchise agreements.

Love,

Cass